9 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

9.1 The Central Problem

Differentiation extracts instantaneous rates. Given position s(t), we compute velocity v(t) = s'(t). Integration accumulates total change. Given velocity v(t), we compute displacement \int_a^b v(t) \, dt. These operations address opposite questions, yet they are intimately connected. If we differentiate to obtain a rate, then integrate that rate, we should recover the original quantity’s total change. Conversely, if we integrate a function to accumulate area, then differentiate the result, we should recover the original function.

This duality is not a coincidence. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus establishes that differentiation and integration are inverse operations, linked by the relationship between local and global behavior.

9.1.1 The Accumulation Function

Fix f : [a,b] \to \mathbb{R} integrable. For each x \in [a,b], we can integrate f from a to x:

Definition 9.1 (Accumulation Function) The accumulation function (or integral function) of f with base point a is F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt, \quad x \in [a,b].

Notation note: We use t as the integration variable to distinguish it from the upper limit x. The variable t is a “dummy variable”—it disappears after integration. The function F depends on x, not on t.

F(x) measures the accumulated contribution of f from a up to x.

If f(t) \geq 0, then F(x) is the area under f from a to x

F(a) = \int_a^a f(t) \, dt = 0 (no accumulation over a point)

As x increases, F(x) accumulates more contribution from f

If f(t) > 0, then F is increasing; if f(t) < 0, then F is decreasing

Example 9.1 (Linear Accumulation) Let f(t) = 2t on [0,3], and define F(x) = \int_0^x 2t \, dt.

For x \in [0,3], partition [0,x] into n equal subintervals. Since f is increasing, using right endpoints: F(x) = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n 2\left(\frac{ix}{n}\right) \cdot \frac{x}{n} = \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{2x^2}{n^2} \sum_{i=1}^n i = \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{2x^2}{n^2} \cdot \frac{n(n+1)}{2} = x^2.

So F(x) = x^2. Notice: F'(x) = 2x = f(x).

The derivative of the accumulation function gives back the original function. This is no accident.

9.2 The First Fundamental Theorem

The accumulation function F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt converts an integrable function f into a new function F. What are the properties of F?

Theorem 9.1 (First Fundamental Theorem of Calculus) Let f : [a,b] \to \mathbb{R} be integrable. Define F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt, \quad x \in [a,b].

Then:

- F is continuous on [a,b]

- If f is continuous at c \in [a,b], then F is differentiable at c and F'(c) = f(c).

Accumulating the rate f gives a quantity F whose instantaneous rate of change is f. The derivative undoes the integral.

Theorem 9.1 says that integration produces antiderivatives \frac{d}{dx} \int_a^x f(t) \, dt = f(x).

This is one half of the inverse relationship.

Continuity of F.

Let x, x+h \in [a,b]. By additivity of the integral (Theorem 8.6), F(x+h) - F(x) = \int_a^{x+h} f(t) \, dt - \int_a^x f(t) \, dt = \int_x^{x+h} f(t) \, dt.

Since f is integrable on [a,b], it is bounded: there exists M > 0 with |f(t)| \leq M for all t \in [a,b]. Thus |F(x+h) - F(x)| = \left|\int_x^{x+h} f(t) \, dt\right| \leq \int_x^{x+h} |f(t)| \, dt \leq M|h|.

Given \varepsilon > 0, choose \delta = \varepsilon/M. Then |h| < \delta implies |F(x+h) - F(x)| < \varepsilon. Thus F is continuous at x.

Differentiability when f is continuous.

Assume f is continuous at c. We must show \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{F(c+h) - F(c)}{h} = f(c).

From Part 1, \frac{F(c+h) - F(c)}{h} = \frac{1}{h} \int_c^{c+h} f(t) \, dt.

Since f is continuous at c, given \varepsilon > 0, there exists \delta > 0 such that |t - c| < \delta implies |f(t) - f(c)| < \varepsilon.

For |h| < \delta, every t \in [c, c+h] (or [c+h, c] if h < 0) satisfies |t - c| < \delta, so f(c) - \varepsilon < f(t) < f(c) + \varepsilon.

Integrating from c to c+h (and noting the integral reverses sign if h < 0): (f(c) - \varepsilon)h < \int_c^{c+h} f(t) \, dt < (f(c) + \varepsilon)h \quad \text{if } h > 0, (f(c) + \varepsilon)h < \int_c^{c+h} f(t) \, dt < (f(c) - \varepsilon)h \quad \text{if } h < 0.

In both cases, dividing by h gives \left|\frac{1}{h}\int_c^{c+h} f(t) \, dt - f(c)\right| < \varepsilon.

Thus \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{F(c+h) - F(c)}{h} = f(c). \quad \square

Corollary 9.1 (Existence of Antiderivatives) If f is continuous on [a,b], then F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt is an antiderivative of f: F'(x) = f(x) for all x \in [a,b].

Remark on discontinuities. Theorem 9.1 requires f continuous at c for F'(c) = f(c) to hold. If f has a jump discontinuity at c, then F may not be differentiable at c, or the derivative may not equal f(c).

Example 9.2 (Accumulation with Discontinuity) Let f(t) = \begin{cases} 0 & t < 1 \\ 1 & t \geq 1 \end{cases} on [0,2]. Then,

F(x) = \int_0^x f(t) \, dt = \begin{cases} 0 & x < 1 \\ x - 1 & x \geq 1 \end{cases}.

At x = 1:

Left derivative: \lim_{h \to 0^-} \frac{F(1+h) - F(1)}{h} = \lim_{h \to 0^-} \frac{0 - 0}{h} = 0

Right derivative: \lim_{h \to 0^+} \frac{F(1+h) - F(1)}{h} = \lim_{h \to 0^+} \frac{h}{h} = 1

The derivatives don’t match, so F is not differentiable at x=1. But F is continuous everywhere—integration “smooths out” jump discontinuities.

9.2.1 Differentiating Integrals with Variable Limits

The First Fundamental Theorem treats integrals of the form F(x) = \int_a^x f(t)\,dt. In many situations, the limits of integration depend on x. The following result extends Theorem 9.1 to this setting.

Theorem 9.2 (Leibniz Rule) Let f be continuous on an interval containing the values of \alpha(x) and \beta(x), where \alpha and \beta are differentiable. Define G(x) = \int_{\alpha(x)}^{\beta(x)} f(t)\,dt. Then G is differentiable and G'(x) = f(\beta(x))\,\beta'(x) - f(\alpha(x))\,\alpha'(x).

By additivity of the integral, \int_{\alpha(x)}^{\beta(x)} f(t)\,dt = \int_a^{\beta(x)} f(t)\,dt - \int_a^{\alpha(x)} f(t)\,dt for any fixed a. By the Theorem 9.1 and the chain rule, \frac{d}{dx}\int_a^{\beta(x)} f(t)\,dt = f(\beta(x))\beta'(x), \frac{d}{dx}\int_a^{\alpha(x)} f(t)\,dt = f(\alpha(x))\alpha'(x).

Subtracting yields the formula. \square

9.2.2 Antiderivatives and Indefinite Integrals

Theorem 9.1 guarantees that continuous functions have antiderivatives. But antiderivatives are not unique.

Definition 9.2 (Antiderivative) A function F is an antiderivative of f on [a,b] if F'(x) = f(x) for all x \in [a,b].

If F is an antiderivative of f, then so is F + C for any constant C, since (F+C)' = F' = f.

Theorem 9.3 (Antiderivatives Differ by Constants) If F and G are both antiderivatives of f on [a,b], then F - G is constant on [a,b].

Let H = F - G. Then H'(x) = F'(x) - G'(x) = f(x) - f(x) = 0 for all x \in [a,b].

By the Mean Value Theorem, if H' = 0 everywhere, then H is constant. \square

Notation. We denote the family of all antiderivatives of f by \int f(x) \, dx = F(x) + C, where F is any particular antiderivative and C is an arbitrary constant. This is called the indefinite integral or general antiderivative of f.

The indefinite integral \int f(x) \, dx represents a family of functions, not a number. The definite integral \int_a^b f(x) \, dx is a specific real number.

Examples:

\int x^2 \, dx = \frac{x^3}{3} + C, since \frac{d}{dx}\left(\frac{x^3}{3}\right) = x^2

\int \cos x \, dx = \sin x + C, since \frac{d}{dx}(\sin x) = \cos x

\int e^x \, dx = e^x + C, since \frac{d}{dx}(e^x) = e^x

9.3 The Second Fundamental Theorem

Theorem 9.1 tells us that integration produces antiderivatives. The converse question: if we already have an antiderivative, can we compute the integral directly?

Theorem 9.4 (Second Fundamental Theorem of Calculus) Let f : [a,b] \to \mathbb{R} be integrable, and let F be any antiderivative of f on [a,b] (i.e., F'(x) = f(x) for all x \in [a,b]). Then \int_a^b f(x) \, dx = F(b) - F(a).

Notation: We write F(b) - F(a) = \left[F(x)\right]_a^b or F(x) \Big|_a^b.

To compute the integral of f, find any antiderivative F and evaluate it at the endpoints. The definite integral equals the net change in F over [a,b].

This is the computational payoff: instead of computing limits of Riemann sums, we perform two function evaluations.

By Theorem 9.1, the accumulation function G(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt satisfies G'(x) = f(x) (assuming f continuous; the general case requires more care).

Since F is also an antiderivative of f, by Theorem 9.3, there exists a constant C such that F(x) = G(x) + C \quad \text{for all } x \in [a,b].

Evaluating at x = a: F(a) = G(a) + C = \int_a^a f(t) \, dt + C = 0 + C = C.

Thus C = F(a), so G(x) = F(x) - F(a).

Evaluating at x = b: G(b) = F(b) - F(a).

But G(b) = \int_a^b f(t) \, dt by definition, so \int_a^b f(x) \, dx = F(b) - F(a). \quad \square

If f(x) \geq 0, then F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt is the area function. The total area from a to b is F(b) - F(a)—the net increase in the area function.

9.3.1 Computing Integrals via Antiderivatives

Theorem 9.4 transforms integration into an algebraic problem: find an antiderivative, evaluate at endpoints.

Example 9.3 (Integrating a Quadratic) Compute \int_0^1 x^2 \, dx.

An antiderivative of f(x) = x^2 is F(x) = \frac{x^3}{3} (since F'(x) = x^2). By Theorem 9.4: \int_0^1 x^2 \, dx = \left[\frac{x^3}{3}\right]_0^1 = \frac{1^3}{3} - \frac{0^3}{3} = \frac{1}{3}.

This confirms our earlier computation via Riemann sums, but with far less work.

Example 9.4 (Integrating Sine) Compute \int_0^{\pi} \sin x \, dx.

An antiderivative of \sin x is F(x) = -\cos x. Thus: \int_0^{\pi} \sin x \, dx = [-\cos x]_0^{\pi} = (-\cos \pi) - (-\cos 0) = -(-1) - (-1) = 1 + 1 = 2.

Example 9.5 (Integrating Reciprocal) Compute \int_1^e \frac{1}{x} \, dx.

An antiderivative of \frac{1}{x} is \ln x (for x > 0). Thus: \int_1^e \frac{1}{x} \, dx = [\ln x]_1^e = \ln e - \ln 1 = 1 - 0 = 1.

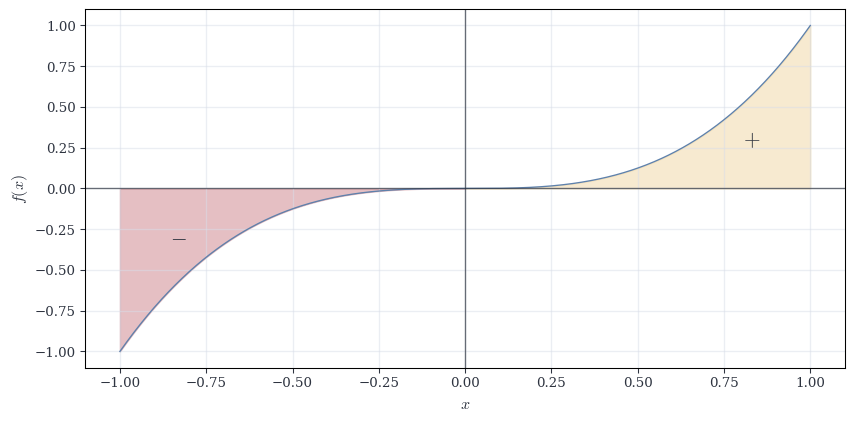

Example 9.6 (Integrating an Odd Function) Compute \int_{-1}^1 x^3 \, dx.

An antiderivative of x^3 is \frac{x^4}{4}. Thus: \int_{-1}^1 x^3 \, dx = \left[\frac{x^4}{4}\right]_{-1}^1 = \frac{1^4}{4} - \frac{(-1)^4}{4} = \frac{1}{4} - \frac{1}{4} = 0.

This makes sense geometrically: x^3 is an odd function, so the area above the x-axis on [0,1] cancels the area below on [-1,0].

9.4 Applications & Extensions

9.4.1 The Net Change Theorem

Theorem 9.4 has a useful interpretation in terms of rates and accumulation.

Theorem 9.5 (Net Change Theorem) If f = F' is the rate of change of F, then \int_a^b f(x) \, dx = F(b) - F(a) is the net change in F over [a,b].

This formalizes our opening intuition: if you know the instantaneous rate at every moment, integrate to get total change.

Applications:

Velocity and displacement. If v(t) is velocity at time t, then \int_{t_0}^{t_1} v(t) \, dt = s(t_1) - s(t_0) is the net displacement (change in position).

Marginal cost. If C'(x) is the marginal cost to produce x units, then \int_{x_1}^{x_2} C'(x) \, dx = C(x_2) - C(x_1) is the total cost to increase production from x_1 to x_2 units.

Population growth. If P'(t) is the rate of population change, then \int_{t_0}^{t_1} P'(t) \, dt = P(t_1) - P(t_0) is the net population change.

Example 9.7 (Velocity and Net Displacement) A particle moves along a line with velocity v(t) = 3t^2 - 6t + 2 m/s for t \in [0,3] seconds. What is the net displacement?

The position function s(t) satisfies s'(t) = v(t), so: \text{Net displacement} = \int_0^3 (3t^2 - 6t + 2) \, dt = \left[t^3 - 3t^2 + 2t\right]_0^3.

Evaluating: = (3^3 - 3 \cdot 3^2 + 2 \cdot 3) - (0) = 27 - 27 + 6 = 6 \text{ meters}.

The particle ends up 6 meters from its starting position.

9.4.2 Signed Area and Absolute Area

The definite integral \int_a^b f(x) \, dx computes signed area: regions above the x-axis contribute positively, regions below contribute negatively.

If f changes sign on [a,b], the integral gives the net area (positive area minus negative area), not the total area enclosed.

Example 9.8 (Signed Area for Sine) Consider f(x) = \sin x on [0, 2\pi].

\int_0^{2\pi} \sin x \, dx = [-\cos x]_0^{2\pi} = (-\cos 2\pi) - (-\cos 0) = -1 - (-1) = 0.

But the graph of \sin x encloses area—it’s positive on [0,\pi] and negative on [\pi, 2\pi]. The areas cancel.

To find the total area (without regard to sign), integrate |f(x)|: \text{Total area} = \int_a^b |f(x)| \, dx.

$$

For \sin x on [0, 2\pi]: \int_0^{2\pi} |\sin x| \, dx = \int_0^{\pi} \sin x \, dx + \int_{\pi}^{2\pi} (-\sin x) \, dx.

Computing each piece: \int_0^{\pi} \sin x \, dx = [-\cos x]_0^{\pi} = -(-1) - (-1) = 2, \int_{\pi}^{2\pi} (-\sin x) \, dx = [\cos x]_{\pi}^{2\pi} = 1 - (-1) = 2.

Total area: 2 + 2 = 4.

General principle: If f changes sign at points c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_k in [a,b], then \int_a^b |f(x)| \, dx = \sum_{i} \left|\int_{c_{i-1}}^{c_i} f(x) \, dx\right|, where we integrate over each interval where f maintains constant sign and sum the absolute values.

9.4.3 Symmetry: Even and Odd Functions

Symmetry often allows definite integrals to be evaluated with minimal computation.

Definition 9.3 (Even and Odd Functions) A function f is even if f(-x)=f(x) for all x.

A function f is odd if f(-x)=-f(x) for all x.

Theorem 9.6 (Integrals of Even and Odd Functions) Let f be integrable on [-a,a].

If f is odd, then \int_{-a}^{a} f(x)\,dx = 0.

If f is even, then \int_{-a}^{a} f(x)\,dx = 2\int_0^{a} f(x)\,dx.

Using the substitution x=-u, \int_{-a}^{a} f(x)\,dx = \int_{a}^{-a} f(-u)(-du) = \int_{-a}^{a} f(-u)\,du.

If f is odd, then f(-u)=-f(u), so the integral equals its negative and must be zero.

If f is even, then f(-u)=f(u), and splitting the interval gives \int_{-a}^{a} f(x)\,dx = 2\int_0^{a} f(x)\,dx. \square

9.4.4 Periodic Functions and Integrals

Many functions repeat their behavior over fixed intervals.

Definition 9.4 (Periodic Function) A function f is periodic with period T>0 if f(x+T)=f(x) for all x.

Theorem 9.7 (Integrals of Periodic Functions) If f is integrable and has period T, then \int_a^{a+T} f(x)\,dx is independent of a.

Moreover, for any integer n, \int_a^{a+nT} f(x)\,dx = n\int_0^{T} f(x)\,dx.

Using the substitution u=x-a, \int_a^{a+T} f(x)\,dx = \int_0^T f(u+a)\,du.

By periodicity, f(u+a)=f(u), so the value depends only on one period.

Additivity of the integral yields the second formula. \square

Periodic integrals reduce global behavior to a single fundamental interval.

9.5 The Inverse Relationship: A Structural Perspective

Let’s make the duality between differentiation and integration explicit.

Define the differentiation operator D : C^1([a,b]) \to C([a,b]) by D(F) = F'.

This maps differentiable functions to continuous functions.

Define the integration operator I : C([a,b]) \to C([a,b]) by I(f)(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt.

This maps continuous functions to continuous functions (and in fact, to differentiable functions).

Theorem 9.1 says: D(I(f)) = f. That is, D \circ I = \text{id} on C([a,b]).

Theorem 9.4 says: If F' = f, then I(f)(b) - I(f)(a) = F(b) - F(a). Modulo constants, I(D(F)) = F. That is, I \circ D = \text{id} (up to constants).

The operators are inverse to each other:

Differentiation extracts rates → Integration accumulates

Integration accumulates → Differentiation extracts rates

This is the organizing principle of calculus: local and global perspectives are dual.

| Differentiation | Integration |

|---|---|

| D : F \mapsto F' | I : f \mapsto \int_a^x f(t) \, dt |

| Local (rate at a point) | Global (accumulation over interval) |

| D(I(f)) = f | I(D(F)) = F + C |

| Sensitive to small changes | Robust to isolated discontinuities |

| Linear: D(F+G) = DF + DG | Linear: I(f+g) = If + Ig |

The Fundamental Theorem unifies differential and integral calculus. They are not separate theories—they are two aspects of the same structure.

9.5.1 When Antiderivatives Don’t Have Closed Forms

Theorem 9.4 is powerful, but only when we can find an antiderivative in closed form. Many functions don’t have elementary antiderivatives.

Examples of functions with no elementary antiderivative:

f(x) = e^{-x^2} (the Gaussian)

f(x) = \frac{\sin x}{x} (the sinc function)

f(x) = \frac{1}{\ln x}

These functions are perfectly integrable—\int_a^b e^{-x^2} \, dx exists as a number. But we cannot express the antiderivative using polynomials, exponentials, logarithms, trigonometric functions, and their compositions.

In such cases, we must:

Use numerical methods (Riemann sums, Simpson’s rule, etc.)

Define new functions via integration (e.g., \text{erf}(x) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^x e^{-t^2} \, dt)

Use series expansions (power series, Taylor series, which we will see in the coming chapter)

The fundamental theorem tells us integrals exist and connects them to antiderivatives. It doesn’t guarantee we can write them in closed form.

9.6 The Mean Value Theorem for Integrals

As a final application, we prove an integral analogue of the Mean Value Theorem for derivatives.

Theorem 9.8 (Mean Value Theorem for Integrals) If f : [a,b] \to \mathbb{R} is continuous, there exists \xi \in [a,b] such that \int_a^b f(x) \, dx = f(\xi)(b-a).

That is, there exists a height f(\xi) such that the rectangle with base [a,b] and height f(\xi) has the same area as the region under f.

Since f is continuous on [a,b], it attains its minimum m and maximum M on this interval (Extreme Value Theorem from Calculus I).

By order preservation (Theorem 8.5), m(b-a) \leq \int_a^b f(x)\,dx \leq M(b-a).

Dividing by b-a > 0: m \leq \frac{1}{b-a}\int_a^b f(x)\,dx \leq M.

By the Intermediate Value Theorem (Calculus I), since f is continuous and takes values m and M, it takes every value in between. Thus there exists \xi \in [a,b] with f(\xi) = \frac{1}{b-a}\int_a^b f(x)\,dx, which rearranges to \int_a^b f = f(\xi)(b-a). \square